“I WOULDN’T DO WHAT YOU MARINES DO

FOR ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD!”

3/3 Reunion Address

Washington, D. C.

17 July 2004

by: John Admire

Second Lieutenant Platoon Commander

2/M/3/3: 1966-67

Thank you for the invitation and opportunity to share thoughts with you this evening. It’s an honor and privilege to be with you once again after almost four decades. We all share many common memories and experiences as well as an abiding respect for our battalion and the Marines and Navy Docs and Chaplains with whom we served. Therefore, this is much more than a reunion; it’s a homecoming for all of us. We’re proud to be with family again.

It’s appropriate to first sincerely thank those who have labored to contribute to the success of our reunion. Doc’s Hoppy and Hardin as well as Bill Lindholm chaired the Reunion Committee and performed superbly. Craig Slaughter, Bob Oberer, Jeff O'Donnell and Doc Hoppy have designed the best Vietnam era unit website that we’ve ever seen. It’s the most comprehensive and current site of its type. To these special Marines and Doc’s and those who supported the Reunion Committee we are deeply indebted. Thank you to all of you.

As honored as I am to be with you, I have a confession. It’s probably the cardinal sin of a speaker to admit this, but I’m somewhat nervous and afraid. As with most of us, we’ve known our share of fear in combat. I’ve served five combat tours as an infantry Marine and often believe that I’m more comfortable in a foxhole with a weapon than I am on a stage with a microphone. Public speaking probably makes many of us feel a little fear. So, over the years I’ve mentioned this during speaking engagements hoping truthfulness would help me feel more comfortable and create a bond with the audience. But on one occasion one of my Marines informed me that "I was a lot more dangerous with a microphone on stage than I ever was with a weapon in combat". This may be a dangerous evening for you since I have the microphone. Stand by.

When Doc Hoppy and Bill Lindholm invited me to speak tonight I asked them if they had any advice on a topic or theme for my talk. In his typical Kansas drawl, Bill simply said, “John, no one will remember a single word you say tonight, but everyone will remember how long it takes you to say them.” Obviously, brevity is the key to success tonight and I promise to be brief. I have only two topics. The Vietnam War was: One, a Tragedy of Misunderstanding and Two, a Triumph of Friendship. We survived its tragedies because of our friendships. It’s friendships that have us together again tonight.

Tragedy of Misunderstanding

The Vietnam War was a tragedy of misunderstanding or misinformation. We’re often described, for example, as bitter, reluctant, complaining, drug culture misfits whose sacrifices were minimal when compared to other wars and veterans. The reality, however, is decidedly much different.

One of the most accurate and authentic polls, the Harris Poll of 1980, confirmed that 91% of us served our nation with pride during the Vietnam War. Our subsequent suicide rates, divorce rates, and success rates are better than the national average of our counterparts from other wars. We never claimed to be perfect, but we served and survived.

Three million Americans served in Vietnam and two million were volunteers. Draftee or volunteer, however, we were simply Marines who served our Corps and Country proudly.

At the time, dissidents claimed we were tactically incompetent. After the war, however, the Communist leadership admitted that we killed 1.4 million NVA or VC. Meanwhile, we sustained 58 thousand killed, which is about a 25 to 1 kill ratio. Maybe we were a little or lot more tactically proficient than some thought. We mourn the loss of every single American killed in the war, but we inflicted our share of losses on the North Vietnamese, too.

The protesters also said it was a small war with small sacrifices and unworthy of their service. They obviously forgot or need to remember that it was the most costly war the Marine Corps has ever fought. Furthermore, we remembered that freedom is worth the fight and sacrifice. For example:

I was taught in training at Quantico that Marine Officers in rifle companies had an 85% chance of being killed or wounded. I learned in combat in Vietnam that the odds for enlisted Marines were far worse. My Platoon sergeant was killed, Right Guide wounded, and three Squad Leaders were killed. Team Leaders came and went too fast to keep accurate records, but most were either KIA or WIA.

The Lance Corporals and PFC’s had even higher casualty rates, but no one needs to tell you that. I had five Radio Operators and two were KIA and two were WIA. In one month I lost two of our Corpsmen.

There is nothing unique in our platoon about these statistics. They’re fairly typical and well known by most all of us and the units in which we served. You and your units probably had similar statistics. It is fate that most of us survived--as well as the courageous and compassionate actions of our fellow Marines and Docs that we came home while many never returned. But if Vietnam was a tragedy, it was a triumph, too.

(The book “Stolen Valor” by B. G. Burkett and Glenna Whitley is the reference for the above statistics that support the theory that Vietnam veterans, as a population, are less troubled, more successful, and better educated than their counterparts from other wars.)

Triumph of Friendship

The Routines and Miseries

The triumph is today in the friendships and camaraderie that have brought us together again. It’s the triumph of the sharing and caring that characterized our time together so many years ago. We endured our share of misery, but that misery is what helped make us who we became and who we are today. The combat actions became major events in our lives, but it was the miserable conditions that we probably remember the most.

Our daily existence in the platoons consisted of combat patrols and ambushes. Day in and day out, night in and night out, the routine was the same—seven days a week, thirty days a month. It rarely changed. Patrols became our way of life and the way to death of far too many of our comrades.

Platoons conducted two combat patrols everyday and one ambush every night. One squad reinforced patrol would depart the base camp lines prior to sunrise and return mid to late morning. One squad-reinforced patrol would depart the base camp lines prior to sunset and return mid to late evening. One squad-reinforced ambush would depart the base camp lines prior to midnight and return prior to sunrise. The patrols and ambushes averaged between four to six hours in duration, six to ten kilometers in distance, and fourteen to eighteen Marines and one Corpsman. It was a small unit and small unit leader’s war. This was our standard routine, but it was occasionally interrupted by what were called battalion “Search and Destroy Operations.”

Whether we were conducting small unit patrol and ambushes or battalion level operations, however, it’s the misery that we probably remember the most.

~The torrid tropical temperatures were often in the 100-degree range with humidity soaring to similar heights. The heat was stifling, especially in the stillness of the jungle with no cooling breezes or the open rice paddies with no shade or protection from the glaring sun. In contrast, the monsoon rains caused constant rain for weeks. We were constantly soaked. In the rainy season in the high mountains the cold temperatures seemed to us as freezing. In all probability the temperatures were probably only in the 50’s, but when you’re soaked to the bone day after day the temperatures seemed much colder. It was always either too hot or too cold. Today, every time it rains, most of us probably remember the monsoon rains in Vietnam. The misery is unforgettable.

The misery of our everyday routine, however, was occasionally interrupted by the “Search and Destroy” operations we mentioned earlier. It’s then that we left the relative safety of our base camps and conducted major operations deeper and deeper into the jungles and mountains and enemy territory. The operations were incredibly dangerous, but they interrupted the cycle of the monotonous routine and misery that characterized our daily life.

The Operations and Actions

A summary of one of our typical “Search and Destroy” operations may help us understand one of the reasons why we can refer to our Vietnam experiences as a Triumph of Friendship as a counter to its Tragedy of Misunderstanding. The triumph is today in the friendships and camaraderie that have brought us together again. It’s a triumph of sharing and caring that characterized our time together so many years ago, but that unites us to this day.

The story I’m about to relate to you is a true one, but it’s the combination or a collage of four or five separate actions into one story. It’s a special story, yet it’s a story familiar to all of us and one any of us could tell it. In this respect, it’s neither my story nor my platoons story, but a story about and for all of us. It transcends time. It’s probably universal to Marines over the centuries. It’s about who we are and what we do. Yet, it’s special, too, simply because it is our story about our time in combat together.

In late 1966 our battalion was issued a “Warning Order” to conduct a “Search and Destroy Operation. “ Unlike the standard, smaller, and shorter duration squad level patrols and ambushes we conducted daily, such operations were usually once every two or three months, normally for three to four weeks in duration, included about 800 Marines and Sailors, and ventured much deeper into enemy territory. The battalion mobilized for a major fight and aggressively searched for the enemy to destroy him.

In the days before the scheduled D-Day we prepared for our departure for an extended time in the field. The day before the operation was to commence, however, the Battalion Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Delong, informed us that a national news media reporter would be assigned to our platoon for the operation. Our primary task was to assure his safety while he wrote an article about “A Day in the Life of a Marine in Combat” or some such title. We were neither excited nor disappointed at having a reporter accompany us, yet hopeful that maybe we’d be mentioned in dispatches. Maybe someone back home, other than our parents and families, would remember that we continued to be involved in a war.

We then helped prepare the reporter for his time in the field. We briefed him on life in the jungle, demonstrated to him the techniques for opening and eating C-Rations, explained a few patrol tactics and immediate actions drills, and equipped him with 782-Gear. He appeared a little nervous by the time we’d talked to him about survival in combat, but we were always a little nervous ourselves. We worried only when we stopped worrying. We guarded against complacency. It’s one basic rule in combat—always worry a little. It helps keep you focused. But worry too much and you become too cautious and maybe too careless. We learned how to worry correctly.

The next morning at sunrise we were heli-lifted into multiple landing zones in the valleys near Khe Sanh and the DMZ. The battalion then advanced west and north along parallel routes as we began to move deeper and deeper into the jungle and higher and higher into the mountains. The first two days were relatively quiet and uneventful, but we anticipated that the enemy would become aware of our presence in time and would seek to either retreat or engage us. In either event, we suspected that day three would begin to become more interesting and more dangerous.

We were on the move early on day three and began our assent into the mountains. The open valleys often provided a sense of relative security because of the extended visibility, but once on the narrow mountain trails and into thick triple canopy jungle, visibility became more restricted and the advance more dangerous. Sensing this, about noon the reporter advised us that he planned on returning to the rear on the next helicopter. He knew that we were normally re-supplied about every three to four days and that this was his ticket back to the rear, clean sheets, hot food, cold drinks, and other such benefits totally absent in the field.

We sort of smiled to ourselves, yet we understood. What was initially planned as a story that would take weeks to research, the reporter had completed in two or three days. He was either a much better reporter than he originally thought or possibly a little fearful as we moved closer to the enemy or simply disgusted with the misery of life in the field. Whatever, none of us could blame him for wanting to return to the rear and a safer environment? Yet, none of us would have left without all of us leaving. We were in it together and we’d finish it together.

As fate would have it, however, that evening immediately prior to sunset the platoon advanced into an enemy ambush. We were somewhat ready because we knew that the NVA would normally try to attack late, surprise us, and then attempt to fade or retreat into the jungle darkness as night fell. Unless totally surprised, the NVA usually fought only on their terms and when we were at a disadvantage. Therefore, we knew that we had to very rapidly gain control with firepower and maneuver. But this was often a major challenge and much more difficult in action than mere words. We knew that knowing what to do and doing it were two different actions. We knew the enemy would do his best to counter our actions as we reacted to his. We did what we had to do.

The stillness and quietness of the jungle twilight were shattered with explosions from mortars, grenades, landmines, rocket launchers, booby traps, and small arms fire from rifles and machineguns. Instantly it was absolute chaos. But we were familiar with chaos. What may appear as total disorganization to the uninitiated was a state we’d learned to live in as well as function in. It was either learn and function or die. We’d been initiated into this chaos time and time again. We learned to function to live.

Immediately, the Marines and Corpsmen in the platoon began to function. With minimal orders or direction from me, they functioned as a coordinated team based upon their training and experiences in past firefights. In seconds we were returning fire and maneuvering. It was imperative that we gain the advantage as quickly as possible or we would be at a serious disadvantage.

One squad held its position and laid down a base of fire to limit or neutralize the effectiveness of the enemy fire. PFC Hossack, my radio operator, despite severe wounds, helped coordinate the actions of the three squads while we called for supporting arms fires and provided radio updates to the battalion for any reinforcing actions. PFC Hossack’s coordinated withering fires enabled the other two platoons to maneuver.

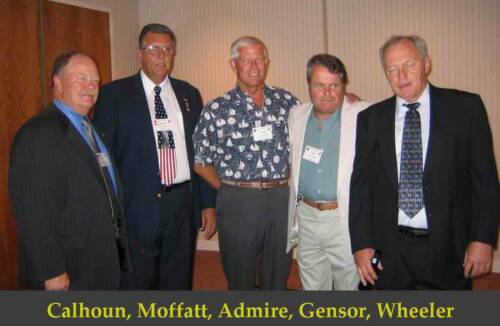

A second squad on the left flank unhesitatingly charged into the killing zone to protect and recover Marines who had been injured or killed in the ambush. With virtually no protection except the cloth of their uniforms, helmets, and flak jackets, they exposed themselves to enemy fire to assist their fallen comrades. Time and time again, Doc Leathes would charge into the killing zone, shield a fallen Marine from enemy fire by positioning his body between the casualty and the enemy fire, pull the Marine off the trail into a ravine or camouflaged area, and medically treat the wounded. Concurrently, Lance Corporal Calhoun advanced into the killing zone to support Marines, redistribute critical ammunition, recover Marines and weapons, and destroy enemy positions. Although rendered temporarily unconscious from an AK-47 round that pierced his helmet and grazed his head, Lance Corporal Calhoun regained consciousness and repeatedly attacked the enemy.

A third squad on the right flank immediately executed an envelopment to further distract the enemy, attack his concealed positions, and possibly intercept any enemy retreat or withdrawal routes. Corporal Wheeler led the attack. With aggressive and accurate fire he first distracted the enemy from delivering fire into the killing zone and then he destroyed them. The enemy quickly recognized Corporal Wheeler and the envelopment as a major threat and turned their attention to him. Although severely wounded and unable to stand, Wheeler crawled forward from position to position constantly confusing the enemy as to his location while delivering extremely effective fire. After about five separate advances by individual NVA soldiers, who were all killed by Corporal Wheeler, the enemy apparently decided to retreat. They’d had more than enough from PFC Hossack, Corporal Wheeler, and Lance Corporal Calhoun.

It was then over as quickly as it had begun. Quiet stillness returned to the jungle as darkness descended. In what had seemed a lifetime, the firefight probably concluded in thirty minutes or so. But such engagements are never over soon enough. By then it was dark, totally dark in the nighttime jungle. No one moved. In this situation you simply held your position. Anything that moved would create noise and any noise was likely to be fired upon. We stayed alert and we waited, we waited for sunrise.

At sunrise we policed the battlefield and advanced to a helicopter landing-zone to prepare for the receipt of supplies and ammunition as well as to medevac our killed and wounded. Once we arrived at and secured the zone the platoon engaged in multiple duties. We assembled together as one squad redistributed ammunition and prepared to occupy an assigned sector of the perimeter, another squad cleaned their weapons and cleaned themselves from the mud and the blood from the battle the night before, and yet another squad tended to the wounded while eating breakfast and helping ready the WIA for their medevac.

As the platoon was performing these duties the news reporter walked up to our location. He was still visibly shaken, almost demoralized, from the chaos and killings and bloodshed from the night before. It had been about twelve hours since the firefight, but it remained somewhat of an emotional trauma to him. Then in a somewhat frustrated or flustered manner, the reporter said “I wouldn’t do what you Marines do for all the money in the world.”

Pfc Smith, a rifleman and radio operator, looked up somewhat surprised and simply said “Hell, neither would we, neither would we” as if to imply who would do this for money. Unfortunately, Smitty was killed a couple of months later by a booby-trapped landmine.

Then Corporal Antoine, a tough Italian Team Leader from either South Boston or Philly, added “There ain’t enough money in the world to pay us to do what we do.” Corporal Antoine was unfortunately killed later that summer by an AK-47 round that pierced his skull.

Finally, Staff Sergeant Cooper, our Platoon Sergeant and former DI, in a rather direct but dignified crusty ole DI growl said “We do what we do because we’re Marines and it’s our mission.” He paused for a moment for emphasis before concluding “We do it because we care for one another, because we love one another as Marines.” Staff Sergeant Cooper later received a battlefield commission to Second Lieutenant and was transferred to the 81mm Mortar Platoon. Unfortunately, he was killed that spring in a rocket attack near Con Thien. His death touched us deeply. He’d recently been on R&R in Hawaii and later informed us that he and his wife were expecting a child—a child he never saw.

At that point the reporter opened his mouth to speak, but no sound was heard. He had talked incessantly the past three days, primarily to interview Marines and Docs but mostly out of nervousness. Now, however, no words came—only silence. Then, somewhat embarrassed and somewhat overwhelmed by the simplicity and sincerity of the Marines’ comments, the reporter simply turned and walked away. There was nothing to say, nothing anyone could add, about such devotion and commitment that Marines have for their Country and Corps. The Marines had said it all. There was nothing to add to the care and love they shared for one another.

At first it seemed that in the midst of the death and destruction and hatreds and angers of war it was curious that Staff Sergeant Cooper would speak the word “love.” In reflecting on it over the years, however, we probably all agree that it was the only word that could be spoken. There is a Bible scripture that states “There is no greater love than one who gives his life for another.” Many gave their lives that we could be here this evening. While we were spared by fate from giving our lives, we were prepared to do so for our fellow Marines and Docs. That’s the essence of Marine love and that’s why we did what we did. We cared for one another then as we do today. There’s nothing more to say.

1966 2004